Lily Xie, Berlynn Bai, Nora Wu

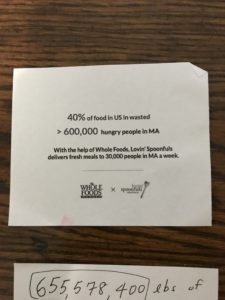

For our project, we partnered with Lovin’ Spoonfuls to create a series of marketing infographics targeted at potential donors in Whole Foods. We started our project with a 30-minute conversation with Liz Ferguson, the Communications & Marketing Director at Lovin’ Spoonfuls. In addition to giving us context on the challenges the organization faced, Liz also provided us with a fact sheet containing their external facing marketing statistics about cost and impact. This fact sheet contained a diverse set of data, including:

- Data about the organization, such as year founded and number of staff

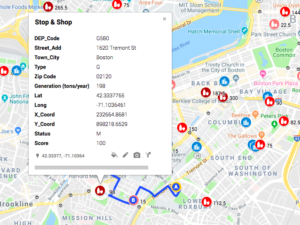

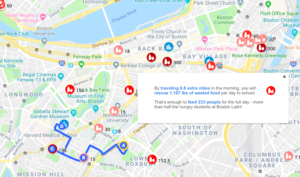

- Geographic data about reach

- Food rescue data, e.g. pounds of food and types of food rescued

- Food donation data, e.g. number of people reached

- Environmental impact data that estimated carbon emissions from food rescued

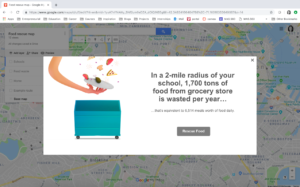

While the Lovin’ Spoonfuls fact sheets was our primary data source, we also joined this with Massachusetts food waste data and Massachusetts Map the Meal Gap food insecurity data.

There was not much cleaning and validation we could do in this case, because the data provided to us was fairly high-level. For statistics that were publically available, such as the conversion of 3 lbs of food = 1 meal, we checked against other sources and studies. Many statistics, such as the reported pounds of food rescued by Lovin’ Spoonfuls in the past year, we had no way to validate.

Because this fact sheet was made to be shared with external viewers, much of the analysis was already done for us. In order to form our full story, we needed to join this data source with some aggregate data around Massachusetts hunger and food waste in order to make conclusions about how much impact Lovin’ Spoonfuls’ work had on total food waste and hunger in Massachusetts.

We wanted to tell a story about the multidimensional impact of Lovin’ Spoonfuls’ food rescue work. In our call, Liz said that one of their biggest storytelling challenges was around succinctly describing their impact on “people, planet, profit”, i.e. the impact their work has on improving health, reducing carbon emissions, and helping organizations profit. Because the audience for our story is anyone who shops at Whole Foods, we did not want to assume much data literacy when telling this story – to that end, we tried to convert the numbers to interpretable units. For example, Lovin’ Spoonfuls included data that their food rescue operations diverted the equivalent of 7,449,521.40 kg of CO2 from being emitted via landfill. From our user interviews, we learned that this number was difficult to understand. To work around this, we decided to instead use a conversion they provided for kg of CO2 to acre of trees planted, then ground that number in a space that Massachusetts residents can relate to (the Boston Public Garden).