Our audience for this teacher-facilitated interactive are middle schoolers in the setting of a nutrition or health class. We chose to target this audience because food insecurity is a newer and more nuanced term than hunger—one that much of the team did not encounter until later on in our educations—but can affect people at any age. Because middle school aged children are beginning to go through puberty, gain autonomy in different realms of their lives and are not the intended audience in any food security interactive we encountered in our research, we thought this provided the unique opportunity to contribute to the available resources and do so for a population not usually targeted.

The data say 12 million American youth experienced food insecurity in the past year. As we embarked on our research, we noted how many resources geared toward youth focused on the causality between abject poverty (often in the global south) and hunger, even though food insecurity is a widespread phenomenon in the United States—even in wealthier, progressive states. We wanted shine a light on this problem at home because food insecurity can have effects on one’s academic performance, energy for activities, mood, physical appearance, and long term health, and we thought it was likely that this audience would not have engaged with food (in)security substantively in their educations, despite certainly understanding the concept of feeling hunger as a universal human experience. The Feeding America dataset is among the most accessible resources available for measuring food access in America, so we wanted to create a resource using this data that teachers could utilize in familiarizing their students with the concept of food (in)security as a localized concept.

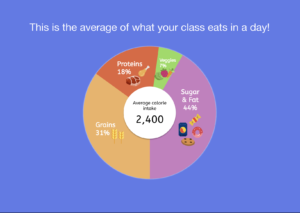

Our interactive aims to provide moments where students’ are co-creating data that can be used to question their assumptions about food (in)security (i.e. in comparing their caloric intake to that of the class, and understanding that food insecurity does not just involve not having any food to eat, but also not having high quality food to eat). The interactive also tries to demonstrate why food insecurity matters to middle school students using accessible examples (i.e. scoring poorly on an exam or not performing well in an athletic competition). Finally, in an effort to avoid imparting widespread anxiety about food (in)security, the interactive includes suggestions of how to combat food insecurity in one’s hometown via ideas like planting food in a community garden or volunteering at a food rescue.

We feel the interactive succeeds in using easily understood, but powerful, data to introduce students to a sophisticated concept, and providing simple examples, explanations, and recommendations that can be absorbed within one class setting. Our interactive could be improved in a myriad of ways including incorporating more types and sources of data (as more youth-specific

or hyperlocal data becomes available) and sharpening the connection between online and offline activities that the students are asked to engage with throughout the facilitation.

Team: Rubez, Wataru, Tanaya