Fuel Frenzy

Tanaya, Melinda, Theresa, Victoria

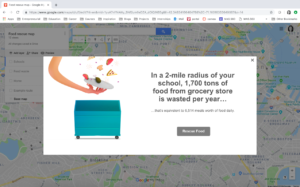

The data say that nutritious eating is complicated–not all foods are equally nutritious even if they’re just as green–and many events may influence the choices a person makes when planning their meals for the week. Additionally, the data say that one tenth of MIT students face food insecurity on campus. We wanted to tell this story because most young adults have not needed to independently choose their diets until they reach college, so this game is an exercise in the challenges and rewards of choosing a balanced diet as an individual, and as a second level, the game promotes discussion within the group about community action on campus related to food insecurity.

Our audience is freshman orientation groups– mostly 17-to-19-year-old MIT “prefrosh” who are arriving to campus and learning about how to live independently. Our goals are to teach the prefrosh how to balance their diets by playing a game that assigns point values to more ‘nutritious’ foods (for example, a bran muffin is worth more points than a serving of pasta) and gives bonuses for a diversely nutritious ‘plate’ (playing a hand with a protein, a vegetable, and a starch gives a point bonus). Additionally, we aim to highlight campus resources such as the ‘SwipeShare’ program that allows students to transfer extra meal swipes to those who need them. A final goal is to show that free food alone is not a consistent or sufficient source of food.

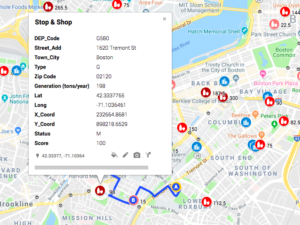

We combined multiple data sources to create the content for our game. By reviewing the foods available in dining halls and those common for ‘cook for yourself’ communities, and by reviewing the Sloan Slack for free food offerings, we gathered the data to inform the list of foods available in the two game decks: personal and free food. We categorized the approximately 40 foods into four categories: Protein, fruits/veggies, starches, and junk food. We then used the USDA nutrition database to assign point values to each food. Proteins were ranked by their protein per 100 grams, starches by their fiber per 100 grams, and fruits/veggies by their total vitamins and minerals per 100 grams. Junk foods were assigned a flat 1-point value.

We determined a point threshold, 10 points, that players are required to meet every turn as a ‘reasonable minimum for survival.’ In future iterations of this game, there may be a consequence for failing to meet this value for a certain number of turns in a row. We also assign bonuses for diverse plates. For example, a plate with 2 categories (ex. protein and veggie) will give a +2 bonus, but a plate with all 3 nutrition categories will give a +5 bonus. Meals composed of junk food never gives a bonus. This rewards healthy and nutritionally balanced eating with points.

We used additional datasets including the MIT event calendar, the CDC Foodborne Outbreak dataset for Massachusetts, and news stories to inform the ‘Event” cards in the game, which introduce an element of randomness. t For example, an event like Campus Preview Weekend increases the available free food. However, an event like a Hell Week increases the required nutrition threshold for the turn, and ‘feeling in a slump’ increases the value of fruits and vegetables. These latter two events highlight the importance of healthy eating not “because we told you so,” and instead link healthy eating to academic performance and mental health.

Prefrosh will be engaged in this game because it begins as a strategic, competitive game. However, at the end of the first half, the orientation leader can lead a discussion about the difficulties of the game, and the advantages that some people may have randomly started with, as some players will have been dealt a stronger hand (this is meant to mimic different levels of food access present on MIT’s campus). In the second half, the game becomes collaborative, and prefrosh are encouraged to talk to each other and share or trade cards so that everyone can meet the nutrition threshold every turn. This accomplishment may give a ‘group bonus’ in the second half, but the details of collaborative gameplay will be worked out in future iterations.