Foodio Kart is an Interactive racing game that helps middle schoolers to learn about how they can make healthy food choices to fuel them and make them thrive in life. The game was built using Scratch.

Victoria Palacin, Rubez Chong, Wataru Doita, Sarah Von Anh

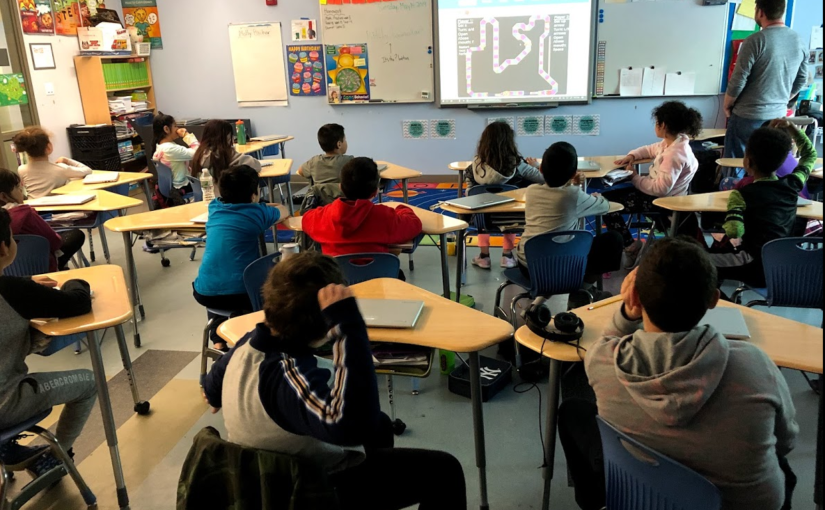

Audience: 21 kids at a local school in Boston, age 8-10

Methodology:

Selected datasets: We combined data from two datasets in order to create a list of food items that could be converted into game elements:

- Nutrition data. Scores of protein and carbs are based on standardized numbers among the choices

- Health score comes from the data of EWG, which are scored by the levels of concerns about nutrition, ingredient and processing

From data to game dynamics:

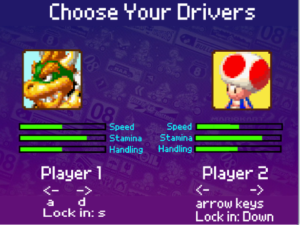

Racers: In the game different characters have different skills (stamina, speed and handling). These skills are intentionally made differently to help kids understand that everyone’s food needs can be different.

- Light Weight: Yoshi, Toad, Peach

- Heavy Weight: Bowser, DK, Wario

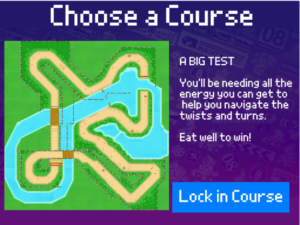

Courses/Routes: In the game, there are 3 courses/routes that the player can choose to play. Each one has a different theme (field day, mind & mood and a big test day ). The courses are grouped into themes to show that different activities can require different nutritional needs and to kids an opportunity to learn food can affect both physical and mental activities.

- Test today: technical

- Field day: fast

- Mood related: sugar crashes

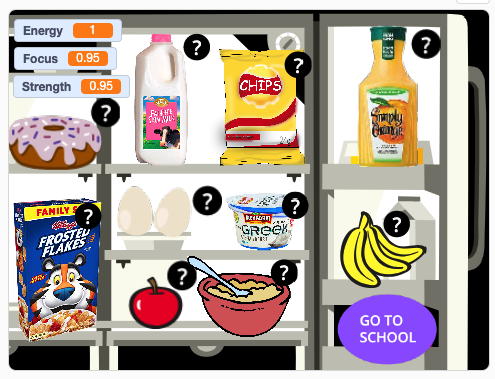

Foods: In the game, food items serve as a fuel with different properties on the game. Table 1 shows the these effects. Players pick their favorite 3 snacks from 9 choices. The snacks a player picked appear on their course. Some of the principles behind the choice of these effects are:

- Max speed: affected by proteins

- Handling / focus: affected by fruit/veggies, healthy fats

- Acceleration / stamina: affected by grains

- Power ups: Vitamins and whole grains

Table 1: Food and their effects on game dynamics

| Food | Value: Protein | Value: Carbohydrate | Value: Health Score* | Game Mechanic: Effect |

| Apple | 1 | 4 | 5 | Boost speed 4 sec |

| Banana | 1 | 5 | 5 | Boost speed 5 sec |

| Orange | 1 | 3 | 5 | Make invisible / force field so can pass through cookie |

| Mixed Nuts | 5 | 2 | 4 | Make smaller so more agile 4 sec |

| String cheese | 5 | 1 | 3 | Turbo boost to end |

| Gogurt | 2 | 2 | 4 | Make slower 3 sec |

| Chocolate Chip Cookie | 1 | 3 | 2 | Boost speed 2 sec sleep 3 sec |

| Potato Chips | 3 | 4 | 3 | Make bigger 5 sec |

| Crackers | 2 | 2 | 3 | NOTHING |

| Bagel, plain | 3 | 4 | 4 | Boost speed a little but for 10 sec |

*Median score in the category here: https://www.ewg.org/foodscores

Impact and Evaluation of Data Game

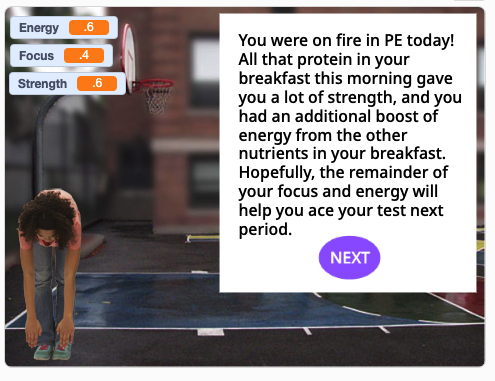

The key goal of Foodio Kart was to educate middle-schoolers on nutritional health and the impacts of different foods on their body. Nutritional data can seem dry and boring; Kids have also heard the same song sung many times. Thus, we wanted to find a new spin on nutritional data by building an interactive game to get kids to “experience” the tangible impacts of different foods on their body via their Mario Kart characters.

Semi-structured questionnaires:

Questions to audience pre-story:

- Have you ever played Mario Kart?

- What do you like about it?

- What is your favorite game?

- Explain why are we here today and our goals

- Introduce ourselves

- Raise your hand if you have questions

Questions to audience post-story:

- How did you like the game?

- Was it easy and fun?

- What was this game about?

- What do you conclude from this game?

- What did you like from the game?

- What would like to change in this game?

- What other types of features you imagine on this game?

How the game works: Kids take on Mario Kart characters and aim to complete a race course. However, the course is littered with all kinds of treats i.e. cookies, chips, apples, oranges, bagels, string cheese. Kids are instructed to eat well as it is their big race day! As they race through the track and pick up these foods, they experience the immediate impacts of the food i.e. cookie – an initial sugar rush and speed boost followed by an energy crash where the characters are forced to take naps, as the other racers speed by. This is an example of how we tried to incorporate tangible impacts of food (via the food nutrition data we analysed) into the game.

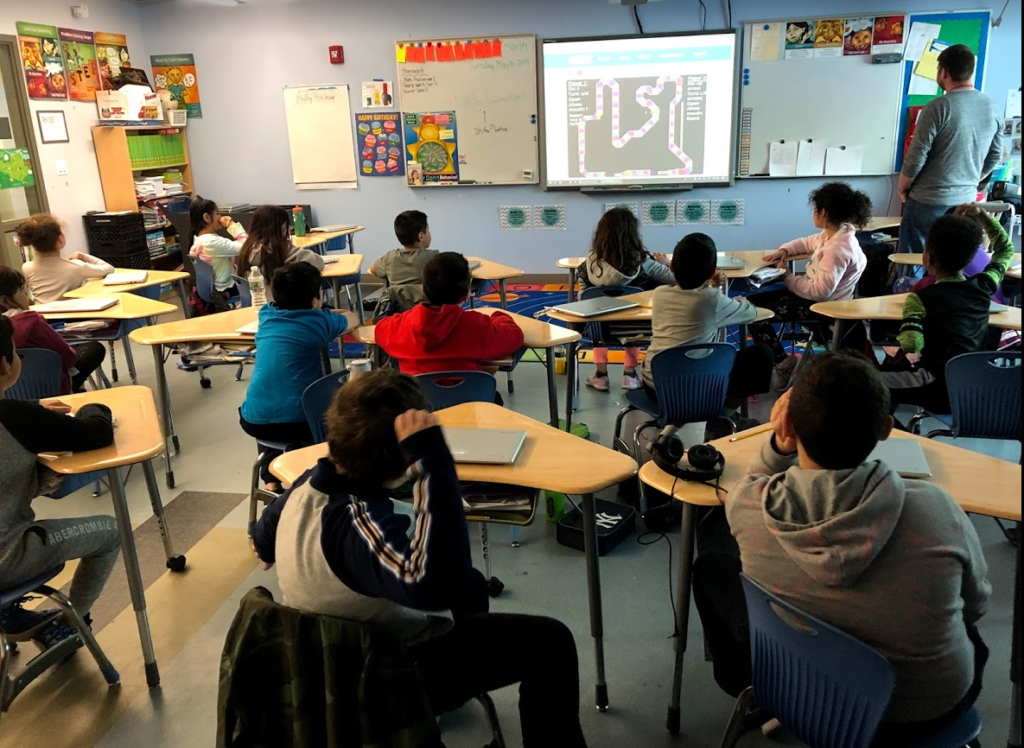

Context for testing: We built the Foodio Kart game in Scratch and brought it for testing at East Somerville Middle School. We had an hour with 21 third-graders where they played the game and the session culminated with a conversation about nutritional health using their takeaways from the game. We also used this time for gathering their feedback on the game i.e. things they liked/didn’t liked/would like to see in the future.

Evaluation

Things that went well:

The kids were really excited about the game and understood the importance of eating well and the impacts of different kinds of food on their bodies. The game provided strong context for diving into a meaningful conversation on food and health. We spent the last 20 mins discussing what it means to eat well and gathering feedback on the game.

Things that didn’t go as well:

We overlooked the logistical challenges that come with working with kids in a school. Firstly, we couldn’t get access to the school’s private wifi and secondly, we didn’t expect each kid to have their own chromebooks (!) We had intended to set up 2 play-stations with 4 kids playing at any one time, as the game was designed as a 2-player experience. This made close observation harder than expected – we were constantly shuttling between the 21 kids.

Further, the game was glitchy and buggy as all 21 kids were playing the game at once. This, in part, took away from the experience of the game. However, all of the kids managed to play the game once and learned about the impacts of different snacks on their “performance.”

Things we would’ve wanted to change:

Whilst we had a meaningful conversation with the kids on nutritional health, it would’ve been better if we could’ve gone beyond the general nutritional discourse on healthy vs. unhealthy food to a more nuanced breakdown of the kinds of nutrition in food, their impacts on health, and a hierarchy of foods – i.e. not all foods are equal – banana vs. apple; though both fruits, affects the body in different ways. We could’ve backed this up with the nutritional data we analysed.

Further, our conversation with the kids helped us realise that it would’ve been helpful to include nutritional/food data as pop-ups in the game to further explain the impacts of food on their character i.e. why the sugar rush and energy crash after eating the cookie.

Feedback and Interview with Kids:

We opened the conversations by getting the kids to tell us their likes/dislikes of the game. To our surprise, the kids were honest and gave us valuable feedback. Many found the graphics and the characters too small. Some expressed that it was different to navigate through the course and some buttons didn’t work for the kids. Some also shared that it would’ve been more impactful if the game was designed from the 1st person viewing angle rather than the 3rd. Finally, the soundtrack was a big hit amongst the kids!