Team Member Names: Lily Xie, Melinda Salaman, Sarah Caso, Victoria Palacin

Data source: Honey Bee Colonies, Released August 1, 2018, by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Agricultural Statistics Board, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Summary: The data say that for small-scale bee farms (5 colonies or less), the colony loss rate is more than double during the winter months compared to the rest of the year. We want to tell this story because, while varroa mites are the biggest health stressors for small and large farms, they disproportionately affect large bee farms and therefore many sources warn beekeepers about mites as the most important stressor to watch out for. We noticed that small-scale beekeepers could save a lot of colonies if they were more prepared for winter, even though the USDA does not list it as a major health stressor in the report.

Audience: Our audience is comprised of small-scale, hobbyist beekeepers that are just getting started with farming bees. They have just purchased a beekeeping kit or joined the “Backyard Beekeepers Association.” They may have done some research about the obstacles to taking care of bee colonies, but are most likely only minimally informed. They also might have seen statistics for large-scale bee farmers and be worried about the wrong health stressors.

Data: Our data source (“Honey Bee Colonies”) is a multi-year report around colony loss in America published by NASS from USDA. This data source contains two pages of insights presented in an executive summary format, as well as a series of charts. The first six charts are full of information about the number of colonies lost, added, or renovated on large-scale bee farms, which they define as having five or more colonies. This data is disaggregated by quarter over 2017 and 2018 (January – March, April – June, etc.) as well as by U.S. state.The next set of charts outlines colony health stressors for large-scale bee farms in the United States, again disaggregated by quarter over 2017 and 2018, as well as by U.S. state. Finally, there was data on the number of colonies lost to Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) on large-scale bee farms in the U.S., broken out by quarter in 2017 and 2018. At the end of the report, the same information is shared about small-scale bee farms (with inventory of less than five colonies), though this is not as disaggregated as it was for the larger farms, and typically presented as annual figures.

We did not consider the quarterly or location-based disaggregated data as useful for our target audience, and therefore looked at these figures primarily as annual aggregates.

To tell our story effectively, we wanted to present 3 pieces of information:

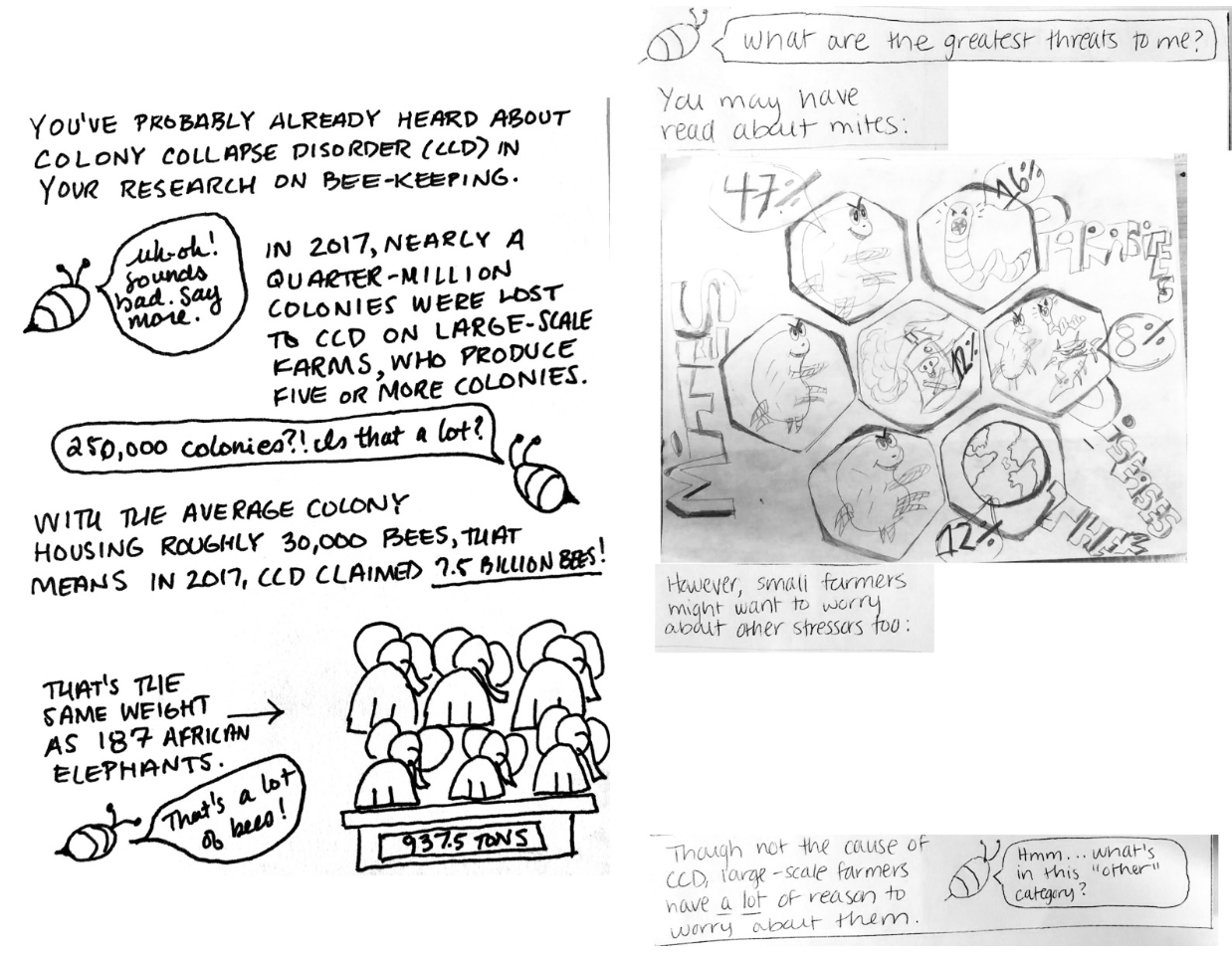

- Scale of colony loss: We start our story by illustrating how many colonies were lost in 2017. While we assume some prior knowledge about loss/CCD, many hobbyists might not know the national scale of the issue. We present the data in a creative chart format that compares the weight of total bees lost to CCD to the weight of nearly 200 African elephants, giving the reader a sense that this is a significant loss of bees worthy of paying attention to. We present this data to show that colony loss is an important problem, and that the viewer should keep reading.

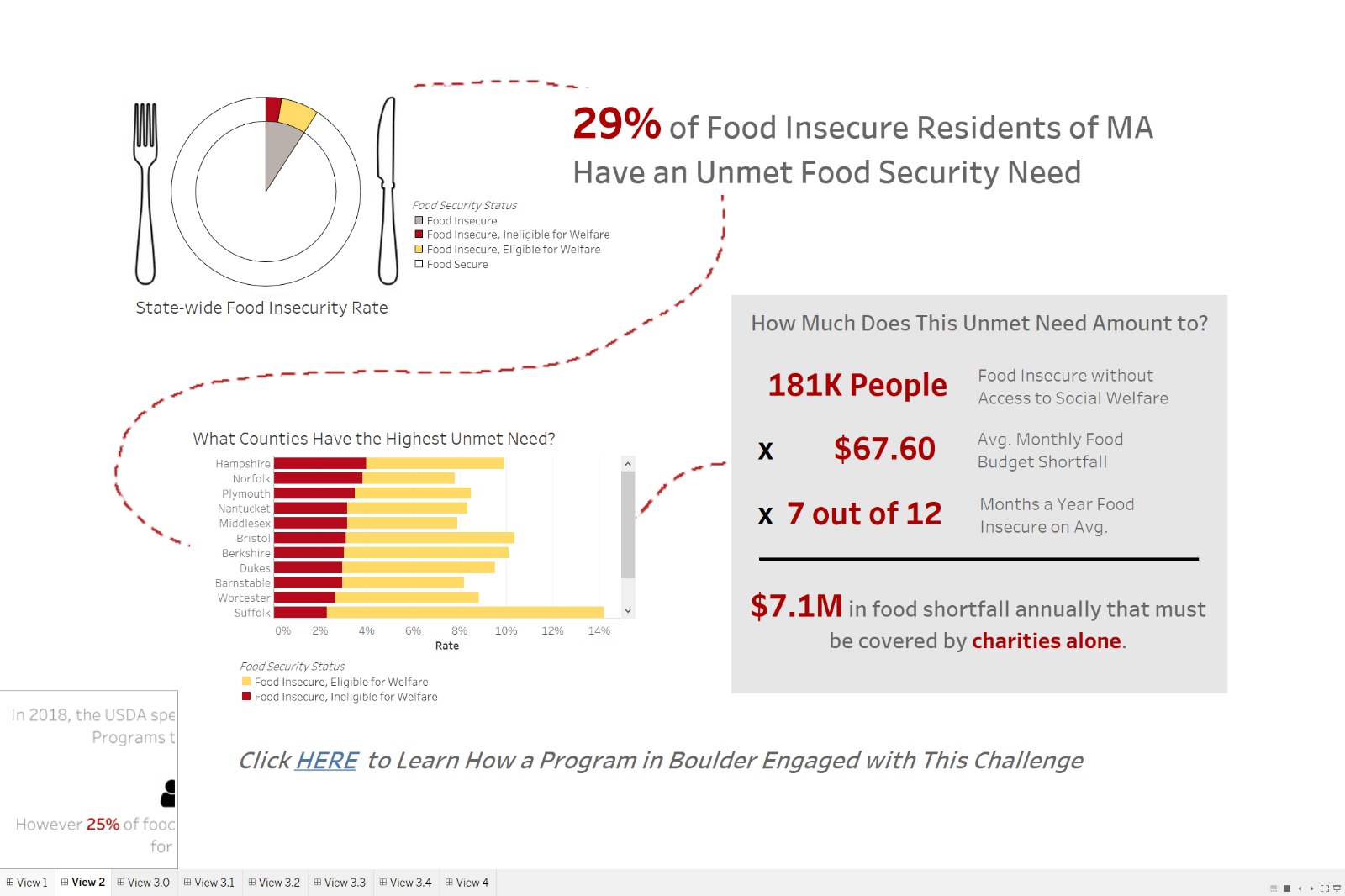

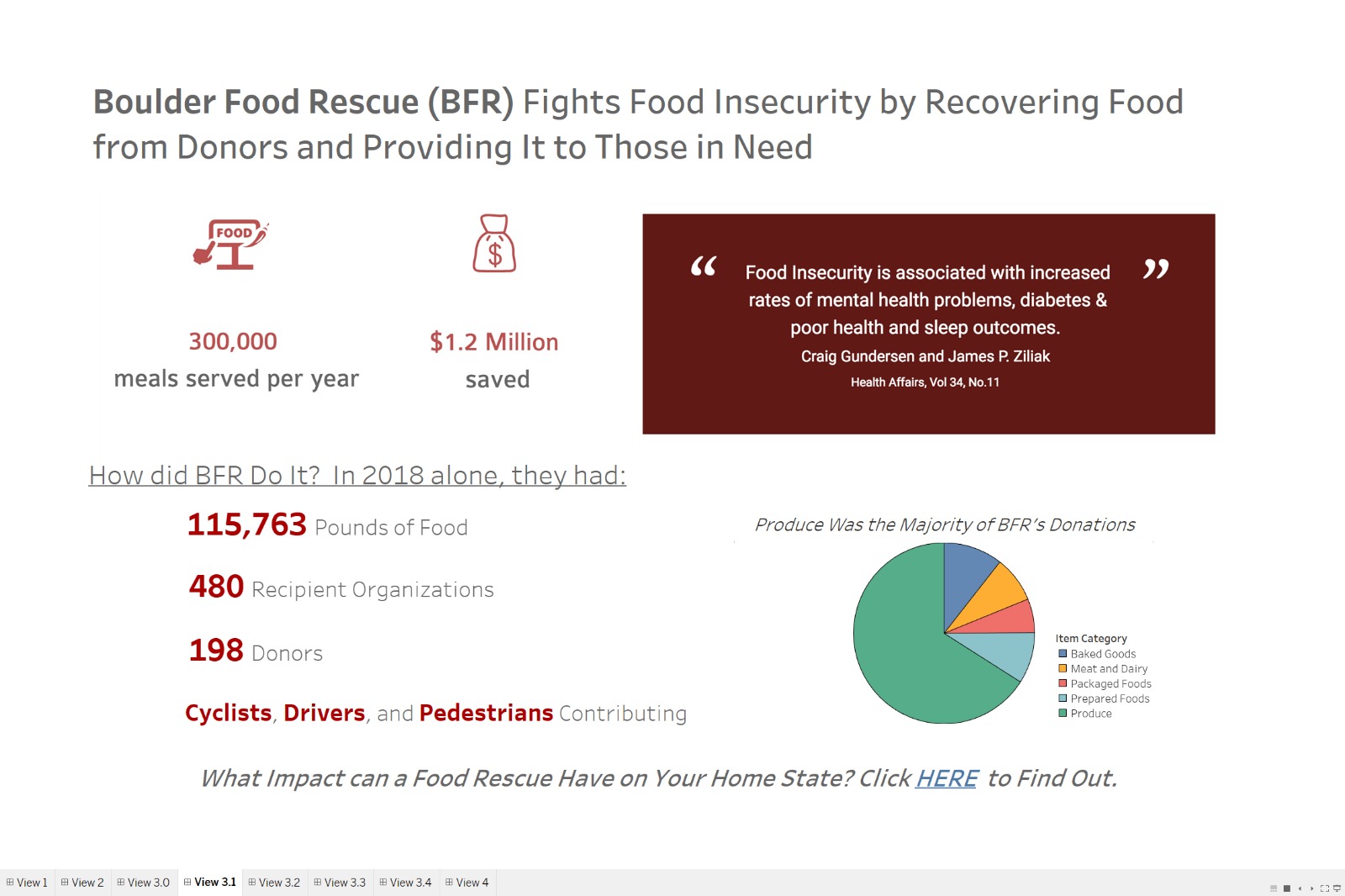

- Common causes of CCD: The foundation of our story is based around the shared understanding of mites, parasites and pests as the major causes of colony loss. In order to start breaking down this assumption, we show the different distributions of large-scale and small-scale stressors. The stressors are presented with stacked creative charts because we want to alert hobbyist beekeepers that the risks they may have read about on the internet for large-scale farms are not quite the same for small-scale farms. Our data shows that mites and pests disproportionately affect large-scale farms compared to small-scale.

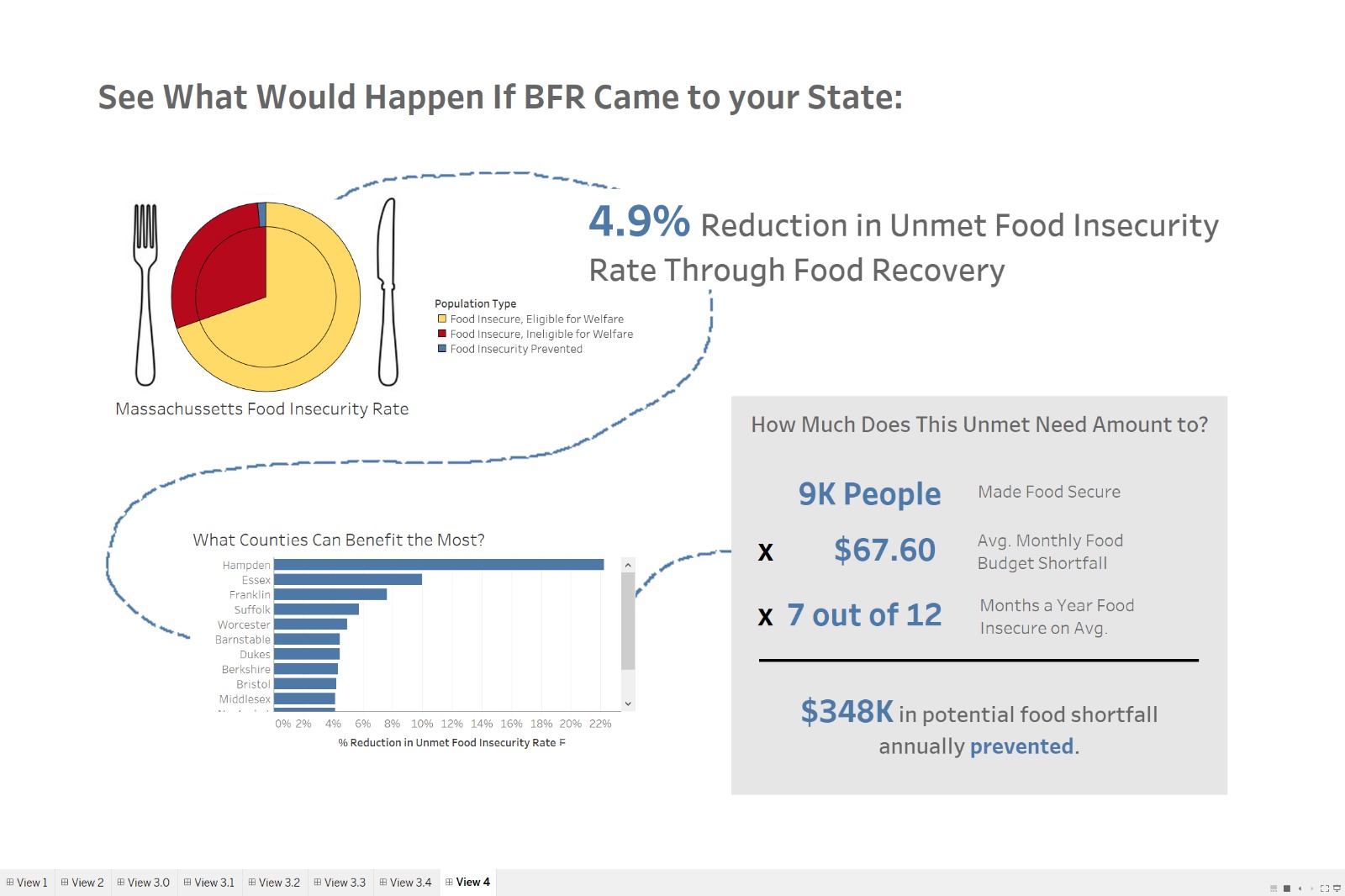

- Seasonality of colony loss for small-scale farms: Our story concludes by highlighting winter as an important cause of colony loss that affects hobbyists but not larger farms. We show the seasonality trends of small vs large farms as a line chart, in order to illustrate continuous trends over time. Our data shows that small-scale farms observe spikes in colony loss during the colder months of January through March, while large-scale farms do not seem to have any seasonality in loss trends.

Format: We decided to make a small pamphlet to describe popular causes of colony loss and redirect readers’ attentions to risks posed by cold weather. Pamphlets are already commonly used for guides and “how-to” literature, so we wanted to present our “Common causes of colony collapse for hobbyists” in a format that matched readers’ expectations. The pamphlet opens up into a 8.5×11 sized poster that shows the impact of winter on small-scale farms and also includes a feeding log that farmers can use to keep track of their winter food supply. We chose to incorporate a reveal into our format because the narrative of our story follows a “setting it up and knocking it down” arc. We use the inner pages of the pamphlet to set up the expectations around common culprits of colony collapse, then use the transition into the poster to involve reader in an “aha” moment and reinforce our narrative with physical action. Our poster also includes a blank log for tracking feeding in order to add some utility to the product. We hope that beekeepers can hang up this poster in their house to serve as a reminder to check in on their bees during the winter and keep track of when the colonies were last fed.